Nursing the Weasel

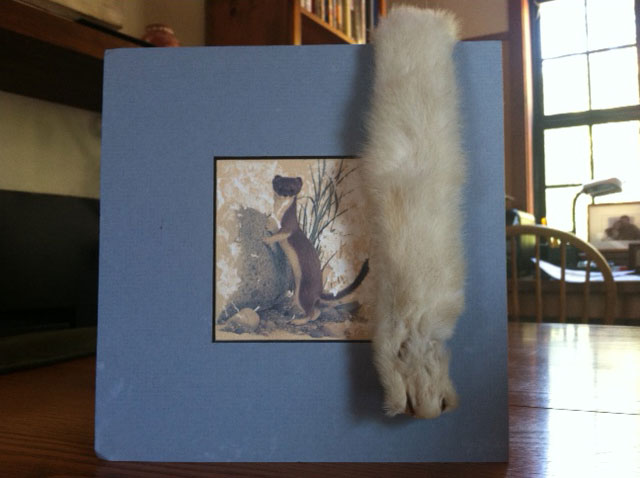

Today I moved my weasel from the bedroom to the office. She’s nice, as weasels go. She measures approximately nine inches in length. Her narrow pelt is soft and white, except for the tail, which is tipped with dark brown like an artist’s brush. Her coloring makes her a winter mammal, I suppose, earning her the more estimable title of ermine. But a weasel by any other name is still a weasel.

My weasel has a tiny tanned nose with two tinier nostrils, rimmed in rose and randomly flanked by long spiky whiskers. Above the nose are a pair of little slanted button holes, gaps which once were eyes.

The mouth is stretched wide in a grimace, or maybe a grin. If I pinch the two sides of her jaw together, as I would a slitted plastic change-purse, poke an index finger into the rift and let go, she dangles from my fingertip, a blanched pendulum of fur. Amazing. Even as an empty fell, she can clamp. With her limp snowy hide and blind stare, she has elegance, power, and a creepy magnetism.

What she does not have is any flesh. That’s my job today, to foster flesh for my weasel.

I. First Date:

This particular stoat arrived by U. S. Postal Service, landing on my doorstep encased in cardboard and covered in stamps. But our first encounter was in a dream.

It was almost a year ago. I was dogpaddling the murky waters of personal transition, and so, as is my wont, steeped in fear. I was recently divorced, dragging myself to a therapist, and skinless from stem to stern. I had even quit drinking alcohol, and could no longer drown my sorrows in Chardonnay.

What can I say? My life wasn’t pretty. I thought I wanted to be a writer, whatever that means, but was mired in procrastination and fear, and in severe danger of wallowing to death. Sure, I had written a memoir and a smattering of personal essays, but I was too terrified to show the work to anybody beyond my writers group, lest I be harshly judged. Paralysis was preferable to sentencing – I had the inner judge and jury confirming that for me daily. Finally, after yet another morning waking up with a bone of anxiety stuck sideways in my throat, I sent out a desperate S.O.S. to the universal powers that be. “Please,” I begged, sitting in the meditation chair in my bedroom. “Please, please. I don’t know what to do. I need some kind of marker, some direction. Help.”

I don’t know what I was hoping for. Maybe a detailed technical manual for middle-aged women in crisis? In any case, what I got was a weasel.

Dream: 3/7/02

I am in my bed, Michael next to me, asleep. The room is dark. As I lie there, I see the bedroom door silently swing open. Two animals slip inside. One is a dog, friendly, harmless. He lies down in the corner. The other is a weasel, light brown, with yellow eyes. Menacing. Furtive. The weasel leaps onto my side of the bed and clamps its jaws into the fleshy part of my palm. I try to pull it off, but it won’t let go. I wake Michael up to show him, but he seems unconcerned about the situation, and rolls over to go back to sleep. I realize I have to deal with this myself.

I leave the bedroom and go out to the patio, the weasel hanging from my hand. I struggle, trying to wrench, then shake it off. Nothing works. I remember my therapist telling me I have to befriend it, so I look straight into the weasel’s livered eyes and say, “What do you want?” Then, reluctantly, “How can I help?”

The weasel loosens its grip, ever so slightly, so that it can speak.

“I think I want to nurse from you,” says the weasel.

Nurse? From me?

“O.K.,” I finally say, “But I’m not sure I have any milk left. I had my children a long time ago.”

I am repulsed, but I shift the weasel sideways, awkwardly. Cradling it in my arms, I lift its weaselly jaws to my left breast. And it starts to nurse.

I watch with horror as the weasel sups contentedly from my bosom. Then its vermine-like features start to soften, to minutely, but inexorably, take on human dimensions. The weasel is transforming into a baby. A girl baby. The weasel/baby lifts her head and says, softly, “Your milk is sweet.” And then suddenly it is me that is nursing, suckling from the Weasel/Woman’s breasts, which are large, firm as melons, and yes, in fact, full of sweet, healing milk.

When the dream ended, I jackknifed awake, thinking: You have got to be kidding me.

I scribbled the dream down on a yellow post-it pad by my bed and read it over a few times. There didn’t seem to be much wiggle room in the interpretation department. I flopped back down.

“I have to nurse a WEASEL???” I yelped to my bedroom ceiling.

You asked, the ceiling replied.

II. Bad Medicine

Some time ago, my friend Carolyn sent me a bright orange book called “Medicine Cards.” Its authors purport to pass along sacred Medicine Wheel teachings from animals, as divined by numerous tribal elders throughout time. I’d shelved it next to “The Road Less Traveled,” “The Ten Second Miracle,” “Healing Runes,” and all my other loyal little books bivouacked on the bedside table like soldiers awaiting their call to arms. Now, I pulled it out. What better place to start my weasel quest?

I looked Weasel up in the Table of Contents. There she was, page 169, sandwiched between Ant and Grouse.

I eagerly leafed to the correct page. I just love research.

“Weasel: Stealth,” I read. “Weasel has an incredible amount of energy and ingenuity, yet it is a difficult power totem to have.” Whoa there, little fella. Who said anything about a power totem? I closed the book. If I’m going to have a totem, it sure as hell isn’t going to be a weasel.

On the other hand, that varmint and I had exchanged milk, kind of the female equivalent of becoming Blood Brothers.

I opened the book back up.

“Weasel ears hear what is really being said. This is a great ability. Weasel eyes see beneath the surface of a situation to know the many ramifications of an event. This too is a rare gift.”

O.K. I could live with that. I started to scan…”If this is your personal medicine, your powers of observation are keen…You might even look a bit guilty at times due to what you know from observing life.”

I glanced up to check the time. I was expected at my friends’ house down the street for brunch in a few minutes. I skipped to the end of the section.

“Look to Weasel power to tell you the ‘hidden reasons’ behind anything. Some people are put off by Weasel medicine, talent, and abilities, but there are no bad medicines.”

That sounded ominous. Whenever I hear a phrase like “there are no bad medicines,” I want to duck for cover. I threw on some clothes and walked to David and L.D.’s house. I needed human company, and strong coffee, not necessarily in that order.

I love Los Angeles. Truly, I do. How can you not love a city where, when asked what you’ve been up to lately, you reply, “Not much. You know, nursing weasels,” and no one blinks.

“Tell us more,” David and L.D. said, drawing in closer. Then their house guest, Lenedra, came downstairs to join us. My stomach clenched.

I had met Lenedra briefly, when the three of them came to my house for post-prandial Thanksgiving pie the previous year. She seemed quiet, but potent, with a coiled inner strength, as if her blond tresses and sweet gaze were accompanied by a double black belt in martial arts. I knew she had managed to transfigure herself from struggling divorced artist to multifaceted businesswoman, helping metamorphose her daughter’s raw musical talent into platinum international success. According to David and L.D., she had accomplished this without compromising her spiritual or ethical convictions. Hah! I thought at the time. Easy enough to make surfing look graceful when you’re riding someone else’s perfect wave of success.

Me? Judgmental? But I adored David and L.D., and they adored her, and as she joined us in the kitchen I decided to give my inner brat a time out.

Instead, I unfurled my dream before them like a rug and we studied warp and woof, looking for the hidden design. Lenedra mentioned a piece on weasels by Annie Dillard. L.D. talked about his own recent, vivid dreams surrounding his father’s death.

“What do you think the weasel is?” Lenedra asked.

“Umm,” I replied.

We moved on, comparing notes on the books we’d both written – mine a very personal memoir detailing the demise of my nineteen-year marriage. Lenedra asked if I had a publisher.

“Not yet,” I replied, before blurting out, “I don’t know what scares me more, that it won’t be published, or that it will.” Flustered, I bit into my bagel, which suddenly tasted like dried animal hide.

“It’s just so…personal,” I added. My friends looked at me oddly, no doubt wondering what the heck I thought a memoir was.

Lenedra’s book was also autobiographical, and about embracing abundance. Hers had just been published. Great. So in her spare time, between negotiating megadeals, she wrote and published a book. I felt the quick, nasty thrust of writer’s jealousy, and automatically flashed a blinding smile, lest I get caught with my shadow showing. Then I fibbed. Said I’d love to read her book. Lenedra, in turn, asked to read my manuscript.

“I’ll try to get you a copy,” I said.

In my next lifetime.

Lenedra’s gaze was thoughtful.

”Maybe your book won’t be published until you find out what you’re afraid of,” she said.

“Is there more coffee?” I asked David.

But as I walked home, it occurred to me that the weasel was already at work. “Look to weasel power to tell you the hidden reason behind anything,” sounded remarkably akin to: “Find out what you are afraid of.” The quick answer was obvious. Without buffers, including alcohol, I was afraid of everything. Whelmed. Directionless. But that was a little vague.

I set the thought aside, deciding instead to take contrary action. I wanted to keep my writing secret, so I packed up two copies of my book, one for Lenedra, one for the boys. I walked back to David and L.D.’s house, and left the pile of typed innards leaning against their front door, like a cat’s quarry. It made me feel good, and brave.

Then I came home, and foraged the on-line Amazon jungle for Lenedra’s book. “The Architecture of All Abundance” soon popped up. First I read the reviews, liberally sprinkled with stars. Highly enthusiastic.

Humph.

I filled out my order, mentally muttering, No title should have that many “A’s” in it. And what did Abundance mean, anyway? It was one of those woolly new age words I resisted, all-encompassing but vague, like Energy, or Empowerment.

I pushed “Send.”

Anyway, just because it had been published didn’t mean she could write.

III: Retreat to the Lair:

O.K. So she could write.

I’d started Lenedra’s book the moment it arrived. It was poetic, funny, and irritatingly appropriate, particularly as it related to, guess what, fear and success issues. I spent two days in bed devouring it, cover to cover, and left a message on her phone with my own four star review. Even riddled with envy, I knew a good set of weasel tracks when I saw them.

A few days later, Lenedra faxed me the chapter ‘Living Like Weasels,’ from Annie Dillard’s “Pilgrim at Tinker Creek.” I’d browsed through Dillard’s book myself years before, but was too caught up in the crowded demands of marriage and motherhood to relate to her solitary foray into the woods. This time through, the vivid and startling depiction of Dillard’s own close encounter of the Mustelidae kind hit me like a fist to the groin. At one point, the sense of deja vu was so strong I actually gasped. True, my weasel had yellowed eyes, hers were of carved ebon, mine slunk in through a dream’s door, hers emerged from beneath a wild rose bush. But the responses evoked by these collisions were of the selfsame, visceral material. Dank and loamy, both our weasel parleys reeked with import and ignited gut cravings to know more.

“I would like to learn, to remember, how to live,” Dillard wrote after her experience. “I would like to live as I should, as the weasel lives as he should… open to time and death painlessly, noticing everything, remembering nothing, choosing the given with a fierce and pointed will.”

All that from one minute locking eyes with a wild mink? Was there some kind of weird sorority emerging here? I combed the chapter for initiation requirements:

“I could live two days in the den, curled, leaning on mouse fur, sniffing bird bones, blinking, licking, breathing musk, my hair tangled in the roots of grasses. Down is a good place to go, where the mind is single. Down is out, out of your ever-loving mind and back to your careless senses…muteness as a prolonged and giddy fast, where every moment is a feast of utterance received.”

There it was. The prescription. Two days in a burrow, in silence, maybe minus the bird bones and skanky fur. A personal retreat, to unearth the hidden meaning of things.

I called a motel I knew in Ojai and booked a room, the closest thing to a den I could find. The decision felt weird, capricious even. For once, I didn’t have to plan around a husband’s moods or my children’s needs. No carpools to reroute, no list of emergency numbers to compile, no pulses to check for potential behavioral upheavals. Except, of course, my own.

Within days, I walked into the small, spare motel room and mentally closed the door to the outside world. Something like relief seeped into my pores. I unpacked my notebooks and clothes, readying my lair. My sleep that night was fitful.

The next morning, I got right to work. Opening a notebook, I referred to Lenedra’s book, and took direction from her own exercises. I wrote across the top of my pad: Success – Money – Me then let my brain relax and my body settle. Yipes. The wash of fear was immediate, and tidal. My first impulse was to fight back, to make a quick phone call to check my messages, or turn on the television set and hear the news, any news. To move, just move, damn it.

I sat.

What is the Weasel? What am I afraid of ?

Flickering pictures. A robed, bewigged barrister pointing at me where I sit in the witness stand. “Unworthy,” the prosecutor declares. In the gallery, my mother and father frown and nod. Next to my parents, my ex-husband, flanked by friends and other family members, inclines his head in agreement, sadly.

My hand started to move across the page.

“I am a kept woman,” I wrote. “Kept perpetually as a child by my financial dependence on my parents and ex-husband. I will never make it.”

My face flushed, as I recalled the trust fund; the years where my “job” consisted of controlling and managing my husband’s earnings; my current alimony situation and parents’ annual gifts, affording me the opportunity to write, regroup, to even be here in this motel. I felt shame around my inherited abundance: where was the book about that?

I swallowed hard, sitting on the bed with my notebook on my lap. There was nowhere I could go. Nowhere, but forward. I wielded my Uniball sword and continued.

“I’m afraid I will never succeed in my own right. That I have nothing valuable to share. That if I stick my neck out no one will care, much less pay me. I’m afraid of being judged and found wanting – that others see me as a spoiled, helpless, profligate, worthless, talentless, lazy, good-for-nothing, entitled, incapable, immature child…”

I groaned. Surfing the wave of another’s success, indeed. Now who was wearing the wet suit?

“I don’t feel like I deserve to succeed. I’m afraid to hope I do. I’m afraid to ask for a chance, to ask for help for anything, scared to really look at what’s possible. I’m terrified to move into my own dreams, to really promote myself, to ask my Higher Power for Its will for me with a clear pathway to more – what – ease? Peace? Power? Riches? I’m frightened to leap.”

I closed the notebook. I had to take a break from all this gory insight. I put on my walking shoes and took off up the dusty road that ran in front of the motel. I walked far enough to work up a small sweat, but the pull to return and worry these raw truths further soon drew me back into my hideaway.

I decided to change course and tackle my animosity toward someone else, a resentment harbored for years and recently rekindled. It was burning me up.

The target was my ex-husband’s previous ex-wife. While we had both since been replaced by a fourth wife, my predecessor was back in a settlement battle with him, and had tried to enlist my help. She was well within her legal rights, but it still pissed me off, triggering old, unexamined enmity. I let my pen run its course, uncensored.

“I resent her greediness, paralysis, inability to move, to be her own woman. Manipulative! No sense of gratitude! Stuck, stuck stuck! “

With the boil lanced, I next considered my own part in the bad blood before me.

“Throughout the marriage, I held the purse strings, played the role of micromanager. I signed the alimony and child support checks. I was comptroller, controller, superior, boss. I was the good wife. I knew how to plan. I was mature, able to budget, save money.”

Yeah. Right. Just like I, unlike her, knew how to stay married. One of us had the good sense to get out early, and it wasn’t me.

I started to write again: “I saw her as greedy, spoiled, immature, weak, incapable…”

Hold on. Hold on. Something about those… I leafed back a few pages. Flipping back and forth, I caught my breath. They were precisely the same words, of course, I had used to describe myself.

Another image arose: my successful husband, lying on his side like a weary sow. A neat little row of piglet ex- and current wives suckled off his celebrity greedily. But the brew, rich as it seemed, couldn’t nourish them. They were all, myself included, failing to thrive.

I stood up again. I wanted to scream, stomp my feet, throw a tantrum. This must be what a toddler felt like when weaned abruptly, after nursing past any nutritional need.

I sat down again. I wrote. Paced. Wrote. Prowled. Wept. Sat. Wrote. For two days, with occasional breaks for sleep, food and fresh air, I pinned my froggy dread to a board and further dissected its entrails. I devised a personal prayer specifically asking for my fear of change to be removed, and added it to my meditation regime. On separate pieces of paper, I jotted down secret ambitions and possible solutions, then spread them across the bedspread, picking up one, then another, pairing them like cards from the game Memory.

I grappled and writhed with multiple incarnations of my slippery trickster of dread, knowing that from a slightly different viewpoint, wrestling and embracing look like the same thing. And somehow, little by little, the fear started dispersing through me, as opposed to running me. I might never stop feeling afraid, but so what?

Before I drove home, I took a stab at a personal mission statement. Why not? I’d started this whole journey looking for a manual, hadn’t I? I concocted one just for me, a storyteller’s business plan. It had to do with radical honesty, and offering hope and ease through exposing frailty and fear. A little New Age-y, perhaps, but it was a start. At least I’d avoided the “A” word.

A week later, I got a parcel in the mail, from Lenedra. I brought it into the kitchen and slit the tape open with a paring knife. I tipped the package over. A soft furry white thing spilled onto the floor.

I unleashed a short bark of delight.

I unfolded her note: “Loved your book. Couldn’t put it down, didn’t want it to end,” she wrote.

I took my weasel upstairs, and laid her along the left edge of the antique desk catty-cornered to my meditation chair, which over time has become a shrine-like repository for the sacred and the silly. Surrendering Buddhas and fossils in stone rub elbows with a fallen Christmas ornament of a heart and sundry goofy baby pictures.

IV: Nursing the Weasel

For months, my weasel kept company with the other talismans, only leaving for the occasional field trip with me, back East to visit my parents, or up North for a meditation retreat. She lay there, patient, as I sat every morning in quiet reflection, then wished me well as I ventured out into the world take risks, to hunt for help and guidance. To follow my own nose. She whispered to me to trust when I got discouraged, to let go whenever I started to grip too hard, and she reminded me that weaned children can and do grow on their own.

I’d love to report that within weeks my book found a publisher, my essays leapt into magazines across the country. I’d love to announce that I knew in a blinding flash what my destiny was, and soon had the title and recognition to prove it. That kind of instant success hasn’t happened. Inroads have been small, progress incremental. But the other day, as I sat down for my morning meditation, I noticed my weasel watching me with her eyeless eyes. I decided to check in on my personal courtroom of finger-shakers – you know the ones, those judgmental voices who love to badger and warn: “You’d better not…” or “How dare you…” or “That’s enough of that, young lady.”

They were all still there, of course, the all-seeing judge, the jury of parents, teachers, my former husband. But they seemed to have switched sides. They weren’t with the prosecution any more. They had become part of my defense team. I was the one who had assumed they all wished me ill. Now the faces were a little more supportive, a little kinder, if suspiciously vulpine.

That’s when I decided the time had come to move my weasel from the inner to the outer workplace. That’s when I carried her to my office to live, the place where I am now paid to craft words of hope for others to read.

She seems to like it here. I think she’s already gaining weight.