Stretching the Truth

Russian Pre-Ballet Conditioning, the flyer on the dorm bulletin board announced.

No previous experience necessary.

“Sounds terrifying,” I said to my new friend. “Not for me.”

I was a college freshman now, and blessedly no longer required to participate in

the endless parade of team sports mandated by my all-girls boarding school. Goodbye,

hideous pleated gym skirts and unyielding shin guards, as I engaged in brutal field

hockey battles, hacking at others with a curved wooden stick. Farewell, interminable

softball games, my chronic daydreaming rudely interrupted by Oh-God-the-play’sheaded-

my-way-at-right-field drama. Adieu, mortifying basketball skirmishes – I was

always the one who air-balled a key scoring opportunity. Now I could choose to engage

in physical activities or not, and mostly I chose not.

But my friend was intrigued by the flyer, with its hint of the exotic.

“I wonder what we’re supposed to wear,” she mused. “A leotard?”

Like the stone sealing off Alibaba’s cave, my resistance dissolved before this

single, magical word.

When I was little, maybe five or six, I attended ballet class briefly. I would gape

in unabashed admiration at the “big girls,” on their way out of the studio. They did not so

much walk as skate, toes out. Their stick-thin legs, encased in pale pink tights, were like

slender stalks supporting graceful Dacron-wrapped flowers. I was deemed “stocky” at the

time. (Nobody used the word “fat.” Nobody had to.) My chunky form, stuffed into

stretchy polyester casing, was more reminiscent of sausage than bloom. For the year-end

ballet recital, I played the proud Moon to a constellation of lithe Stars, sidekicks to a

gazelle-like goddess in white tulle pirouetting alongside us. My lumpish leotard was

topped by a foil, crescent-shaped crown that bobbed and swayed overhead and

presumably distracted from what was going on underneath.

But that was then. I had lost the baby fat, aided by genes and a recently adopted,

top-secret diet plan so novel it didn’t yet have a name but involved daily binging and

purging. This class was my chance for a dancewear do-over.

We paid a visit to the local Capezio store, a treasure trove of frothy tutus, satin

Pointe shoes, and a multicolored array of Lycra leotards. My friend, sensibly, chose

black. Inexplicably, I went with bright purple: the color of royalty, passion and,

unbeknownst to me, imminent persecution.

The flyer turned out to be false advertising. Our teacher, a withering martinet, was

the only “Russian” element in an otherwise fairly straightforward calisthenics routine.

She made the most of her heritage, however. Short and squat, she barked commands so

heavily underpinned with Slavic menace we might as well have been soldiers on a

Siberian Death March.

“You in zee purple! No! No! No!” she would shout as I tried my awkward best to

reach, stretch and fold, a flailing flag of violet in a sea of anonymous black. My friend

and I lasted about a month, and I dropped out with a deep sense of relief. I would have to

find physical conditioning elsewhere, if not give it up altogether.

But the purple leotard instantly became my favorite top. Paired with low-slung

bell-bottom jeans, or worn under painter’s overalls, it sent a mixed message to boys, one

that perfectly mirrored my own state of carnal confusion. “Check this out,” the leotard

seemed to say, and at the same time, “ne touche pas.” It promised, even as it deflected.

Soon, black and navy versions joined the purple, and leotards became a daily staple.

The value of chaste clothing had been drummed into me as a child, and was

further underscored at my all-girls Episcopalian boarding school. Modesty was next to

godliness. I’d arrived at Radcliffe determined to scrap this notion, but I was scarily

inexperienced. What if a risqué choice invited more male attention than I knew how to

handle? A leotard seemed to solve both issues. Sure, spandex revealed things, but the

tight material also made it difficult to actually get to those things. And if my strutting

around in a long-sleeved, skin-tight body suit was a form of misdirection, I could live

with that, too. No one need know that I’d never actually… that I was still a… that in

some ways I remained the chubby Moon who’d never graduated to grand jetés.

Time passed, and I slowly grew more comfortable with my new college self. I

migrated to the Harvard campus sophomore year as part of the awkward and ongoing

“non-merger merger” of the two institutions, and secretly celebrated the four-to-one

male-to-female ratio that came with the change of address. I added ribbed tank tops,

mirrored mini-dresses, and embroidered Moroccan frocks to my repertoire. Still, when a

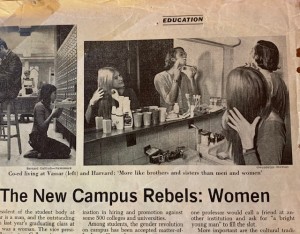

Newsweek photographer showed up on campus junior year and asked me to pose for a

photograph that would accompany an article on “Women as the New Campus Rebels,” I

knew exactly what to wear.

Rebel—I liked the sound of that. Maybe I finally qualified. I’d marched against

the Viet Nam War. I’d jettisoned my bras. I’d smoked marijuana. I’d not only had sex

with a boy, I’d figuratively and literally moved on from Radcliffe’s cramped, sherrysipping,

rule-burdened dormitories (“No male overnight guests! Doors must remain ajar!

Three out of four feet must be on the floor at all times!) to the looser, and, let’s-face-it,

far more exciting “Houses” on the Harvard campus. A Radcliffe rebel doing her part,

joining the initial test-batch of female transfers, contributing to a social experiment with

an eye to more expanded co-ed living down the line.

My Harvard home, Adams House, had been built in 1931, fulfilling parental

demands for appropriately luxurious accommodations for their entitled male offspring.

Three- and four-bedroom living-quarters included a shared living room and bathroom.

The design reeked of built-in privilege, with a smaller bedroom tacked onto every suite—

you know, for the valet. More private men’s club than dormitory, Adams House had

wood-paneled walls, gilded sconces, a billiard table, and even an indoor swimming pool

in the basement. There, bathing suits were not required for haughty young stallions with

names like Roosevelt and Hearst and Kennedy.

Somehow, and somewhat suspiciously, someone forgot to change this rule when

Harvard decided to move in some fillies.

I’d always loved to swim, and here was an actual pool, just a quick trot down

three dark staircases. Exercise, on my own terms! No taking orders from a deranged Slav!

No gym skirts, much less bathing suits, required! I tiptoed into the dank, chlorine-infused

room early one morning to test my resolve to be less modest—less hung up. The pool

was sunken, and surrounded with tiled walls and a small exposed changing area with

mounted showerheads. My eyes were drawn to a sole figure swimming laps. Jane. I’d

seen her around, sipping black coffee in the dining hall, traversing the quad, crossed arms

protecting her hunched body. I’d also registered, almost unconsciously, how she was

slowly disappearing, like a penciled drawing whose outline was fading. Now I watched,

curious, as Jane churned through the water, her skeletal frame and determined back-andforth

grind hinting at compulsion more than recreation.

I slipped out of my leotard and jeans, my cotton underpants. I darted into the

water, quick as a lizard. Pushing off the slick wall, I started to glide, just under the

surface. Cool water enveloped my skin, liquid and forbidden. I felt like a Naiad, or better

yet, a Siren, part of a secret, mythological world. I was hooked.

Every day, Jane and I shared the pool for our morning swim, though she was

always well into her laps when I arrived, and still rounding her turns when I left. Even

underwater, her shoulder blades jutted like pinions. I sensed something was wrong with

her, but had no words to put to it. No way to connect Jane’s compulsive behavior to my

own ongoing, volatile relationship with food.

Years later, well into my own recovery, I would learn from a mutual friend that

not long after our graduation, Jane died of a heart attack, a brutal side effect of her

chronic anorexia nervosa. She was twenty-five years old. I could have been her.

I soon grew bold about swimming naked — some might say shameless. The water

caressing my bare skin felt natural, and nudity became normal. I loved morning laps with

my gaunt companion, and I loved evening pool-time, splashing and diving with naked

male and female classmates like a colony of seals. It helped that I was too near-sighted to

see much of the equipment around me, which allowed me to falsely conclude that others

couldn’t see mine. It’s hard to believe now, but I never felt threatened, not once.

The Newsweek photographer, thankfully, had not gotten wind of the nudie goingson

in the basement. She was there specifically to capture the “co-ed bathroom”

experience in Adams House, even if we were experiencing no such thing in our gendersegregated

suites. I was game, but I needed to find a friendly male who would join me in

the hoax. I knew exactly who to ask, and my buddy Tad instantly agreed. Fake news or

not, this sounded like a hoot.

Tad was like that – a dependable pal, always up for adventure, and the opposite of

threatening. He was tall and lanky, with blond curls, a wry, wicked wit and eternally

amused eyes. At the time neither he, nor I, knew why we felt so safe with each other. A

decade and a half later, lying in twin beds in a darkened dorm room at our fifteenth

reunion, I would finally broach the subject, although my route was circuitous. I had

already lost one friend too soon. John was a banker, born the same year as me. He’d

perished from a terrible and mysterious disease wreaking havoc on his community, his

friends too afraid to visit him. I’d arrived at his hospital bed with a carton of ice cream

moments after he died, skin blackened and piebald with sarcomas. It was the first and

only time I have experienced tears shooting horizontally from my eyes, as if propelled by

a gut-punch of grief.

“Tad?” I now ventured, protected by darkness. “I have to ask. Have you been

tested?”

His answer floated back, a feather. “Yes.”

“And?” I held my breath.

“And no, I don’t have it.”

My eyes stung in the shadows. “Thank God,” I said. I pressed on. “I’m really

sorry. It must have been hard back then. I… I didn’t know you were gay.”

“Honey, how could you?” he answered, his voice laced with amusement. “I didn’t

know myself. I mean, who even had the vocabulary?”

There weren’t words for a lot of painful things in those days, but we muddled

through, bound by affection and shared confusion. When the day arrived for the photo

shoot, I pulled on my purple leotard and hip-hugger jeans, and stood beside Tad, facing

the bathroom mirror of my all-girls suite, where no boy ever ventured. I was directed to

pull a brush through my curtain of hair. Tad, to foam up his smooth-skinned, whiskerfree

cheeks and clear a path with his razor.

The photograph appeared in Newsweek on December 10th, 1973. The caption

beneath it read, perhaps prophetically, “Co-ed living at Harvard: more like brothers and

sisters than men and women.” Rose Mary Woods graced the cover of that same issue,

stretching her own version of the truth as she reenacted her human-pretzel imitation while

erasing Nixon’s Presidential misdeeds. Both snapshots depicted totally contrived

moments.

But ours was also a moment of truth. The narrative may have been false, but the

connection was genuine. The photograph captured the burgeoning bond between two

innocents—a young woman in a purple leotard, and a young man in need of a beard. We

were harboring inexpressible secrets, forging intimacy in the face of perplexity—the

embodiment of valiant fronting, callow connection, and a friendship that, like Tad, like

me, has managed to survive.